It's true that all popular music tends to revolve around the same themes--love, heartache, jealousy, pride. And all popular music tends to also explore themes or experiences common to everyone's life--death, money, joy, violence, playfulness, melancholy, sexuality. But African American musicians have had to make their music under an unusual set of circumstances.

African Americans combined their various African traditions with European musical forms to produce a distinctive, vibrant musical style. Early on, as early as the American revolution, white audiences recognized the distinctive qualities of African American music, and began to imitate it.

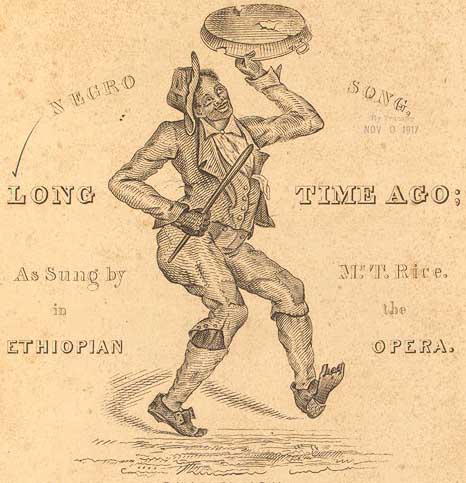

The most disturbing form of this imitation developed in the 1830s, in what became known as the "minstrel show." In the minstrel shows white men dressed up as plantation slaves. Faces "blacked" with greasepaint, they imitated African American musical and dance forms, combining savage parody of black Americans with genuine fondness for, and interest in, African American culture.

As you can see, the images of minstrels were buffoonish and insulting. But the music they sang, while most often written by whites, drew directly on melodies African Americans sang. In this way, African American music first entered into popular culture. Most of the classic American songs of the 19th century, including Camptown Races, My Old Kentucky Home, Way down upon the Swanee River, Dixie, and virtually all songs by Stephen Foster, were written for the minstrel show. By the Civil War the minstrel show had become world famous and respectable.

The minstrel show usually made black Americans into grotesques. But it's also clear that white Americans, then as now, were strongly drawn towards the creativity and vibrancy of black culture. The minstrel show allowed them to play out fantasies that ordinary life forbid, but it also created a vast audience for African American culture--an audience willing to pay for songs and performances. By the 1890s there were many African American minstrel performers, all of whom had to "black up" to make money. Not only did they wear the minstrel's black greasepaint, they also had to sing songs and act in ways that conformed to white people's prejudices. These two sites offer more information on the minstrel show before the Civil War.

Blackface minstrel shows continued well into the twentieth century. The first "talking picture" the Al Jolson film The Jazz Singer (1927) was a blackface film, and major white entertainers like judy garland, Mickey Rooney and Bing Crosby all performed in blackface. At first, actual African Americans were not allowed on the minstrel stage. But by the end of the nineteenth century, as the minstrel show became more respectable, African Americans began performing "in blackface" as well. In the 1890s, some of the most important African American composers got their start performing minstrel songs.

The bizarre minstrel show might be easier to understand in modern terms. Think of white rappers like Eminem, or white rock musicians who play blues-derived music. There are many white people who love African American music but don't particularly like African Americans. When they imitate black musicians, are they expressing admiration, or are they just stealing? Are they sincerely trying to come to some understanding of cultural difference, or are they just engaging in minstrel parody without the make up?

Consider also that the largest audience for rap and hiphop music today is white, just as, in 1890, the largest audience for sheet music and music performance was white. MTV, when it shows music videos at all, tends to show rap, especially hard edged rap that features an emphasis on violence, hostility to women and flashy materialism. Record companies, theaters, and stores—the distribution system that publicizes music and gets it to the buyer's hands—are still overwhelmingly owned and controlled by whites. Many critics have pointed out a similarity between the minstrel show of the 1890s and the rap music of the 1990s and now the 2000s

[original writer Michael O'Malley, Associate Professor of History and Art History, George Mason University titled A Bad Rap]